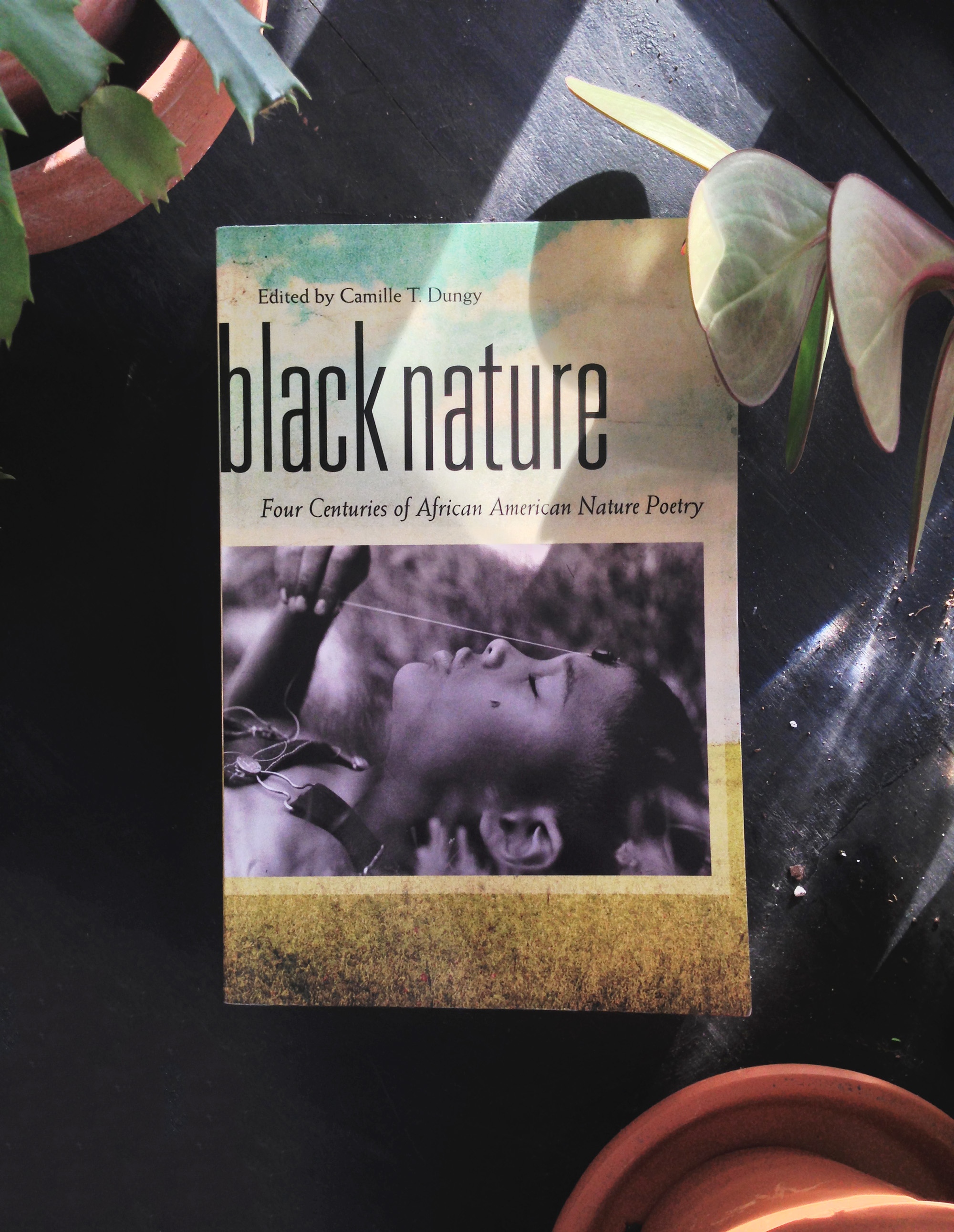

Reading: Black Nature

If we hurried, I could see it

before it closed to contemplate

becoming seed.

Hand in hand, we entered

the light-spattered morning-dark woods.

Where he pointed was only a white flower

until I saw him seeing it.

from “Ruellia Noctiflora” by Marilyn Nelson

Poems can be tough. I remember in grade school we all thrilled when our teachers introduced a unit on poetry, expecting the work to be quick and the homework painless. But we quickly discovered poems to be self-sustaining universes; each line its own world, each word a city block with millions of possible meanings.

In “Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry” editor Camille T. Dungy has invited readers to reconsider the anatomy of the nature poem, and to reconsider the cultural and ethnic makeup of that poem’s author. Since being brought to the new world, Africans and African Americans have cultivated a unique, complex, and often fraught relationship with the land. These poems shed light on the pain and the reality of that history. And they also celebrate it, observing the beauty of the Earth, and our own beauty within it. Even works written from the city dweller’s perspective sound and feel different when read through nature’s lens.

The collection is organized into ten thematic cycles, each introduced with an essay written by one of the anthology’s represented poets. Themes include observation (the elements of the Earth, the beauty of living beings, finding ourselves in nature), confrontation (what happens when the land turns its back on you, natural disasters, and violence bestowed on us in this place), and reconciliation (largely embodied in the gorgeous-from-start-to-finish section titled “Comes Always Spring”).

The poems are beautiful. Some are angry and difficult. Most demand multiple reads — if not for comprehension, then for wanting to be enveloped just one more time. Each poem opens up its writer’s world, just a little, inviting you in to find yourself and your own experience between the line breaks and punctuation. As poems, they are evocative and insightful. As nature poems, they are gloriously visual and sensual. As black nature poems, they are all of the above, as well as indicative of our particular experiences as keepers, stewards, and inhabitants of this land.

My favorite aspect of the collection was the conversation each cycle of poems opened up between the pages and generations. The sections aren’t organized chronologically, so words written in the 18th and 19th centuries, by men and women born into slavery, share space with pieces written just in the past decade. As the book unfolds, the reader can’t help but gain a clearer understanding of the depth and history of our relationship to the Earth, discovering that even as time may pass, many things have stayed the same for us. Fascination with the world’s wild species. Fear of nature’s wrath, and the wrath of those we may encounter within it. Pride in the land, and pride in our own resilience. And joy and delight in the inevitable return of Spring.

This is a wonderful collection, one that I devoured during my daily commutes, saving me from myself during so many furious, traffic-bound bus rides. It introduced me to writers I hadn’t heard of, and reminded me of writers I’ve been wanting to return to. It also introduced me to myself, to a tradition that I’m clearly part of, to a legacy of listening to and learning from the Earth. A legacy that stretches far beyond me in both directions.

One thought on “Reading: Black Nature”