Weeds

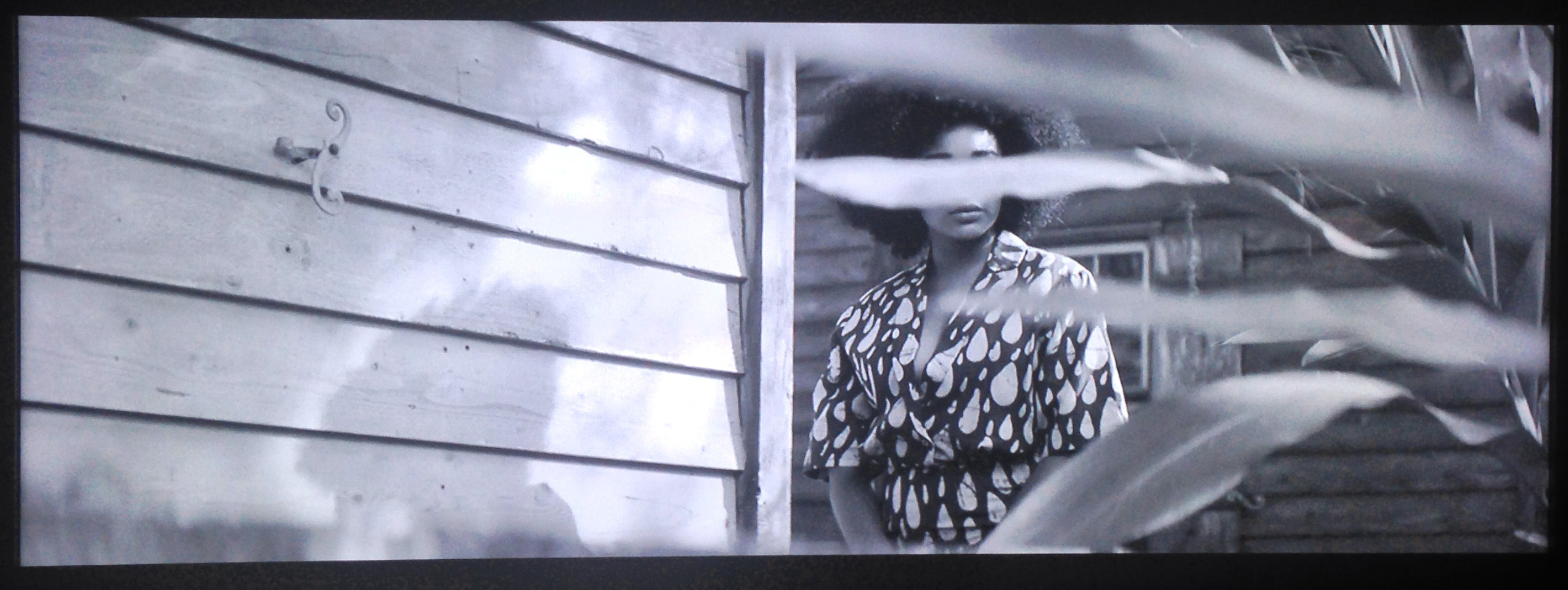

These days the hard asphalt feels miles thick. Solid. Impenetrable. The endless sidewalk unrolls for blocks, dirtied bubblegum dotting the peeling curb, crumbling and worn by the hot summer sun.

My eyes, magnets for green, spot the plants squeezing through cracks in the street. Many like to call these plants weeds. Nuisances, pests. So-called invasive or foreign species, identified as outsiders. Aggressors gobbling up space and resources. Taking hold in soil never meant for them.

In this country, black people are weeds. Brought over from a foreign land, we were cultivated, domesticated, beat back, and disposed of when deemed too wild or unprofitable. We’re seen as opportunistic and greedy. Our features are considered vulgar and undesirable. Experts gather to discuss methods of blocking the spread of our blight. And we’re deliberately eliminated — razed when we take up too much space, destroyed when we simply try to exist somewhere we’re not welcome.

There are things I know how to talk about because I know them so well. And then there are things I struggle to talk about because I know them so well. The helplessness of seeing people that look just like me be systematically overlooked, held back, locked away, and murdered. The hopelessness that comes with learning our history, discovering that the oppression may have shifted gears, but that it’s never really gone away. The frustration of witnessing people continuously deny and belittle experiences they have never had and could never have. The resentment from watching those people speak for me and down to me. The confusion and anger from knowing that some minds can never be changed, that some people will never recognize their privileges, that some truths will never be acknowledged. The emptiness I feel when the dizzying thought crowds my mind: what if justice is an impossible, unattainable dream?

I’ve been keeping an eye out lately for construction zones, not for the buildings in progress, but for the plants that often take advantage of the newly open space. It seems that the rigid asphalt can actually be broken away quite easily — like the shell on a hardboiled egg — revealing the loose, damp earth below. In some emptied lots, the prairie has already rushed in, that grassland that develops after the humans have gone and the earth is left to settle and heal itself. The place where weeds and wildflowers sprout freely, plants differentiated only by context and perspective.

Many of these pop-up gardens won’t make it past the summer. They’ll be sprayed or chopped or smothered. And many of us won’t make it another year. Black people continue to be murdered, black communities continue to be fragmented, our voices continue to be drowned out. But despite their attempts at mowing us down, we keep rising up. We keep growing. We evolve. We sprout thorns to protect ourselves. We blossom.

I have a soft spot for weeds. Unwanted. Misunderstood. They persevere, finding the will to thrive under less than ideal circumstances. They get cut down, pushed over, uprooted, and they keep coming back, stronger than ever. They are resilient. They are beautiful. And so are we.